Researchers at the University of Oxford’s Department of Chemistry have solved a longstanding archaeological mystery by confirming that an orange-brown residue found in ancient bronze jars

is, in fact, degraded honeycomb. Their findings, published in the *Journal of the American Chemical Society*, mark the first biomolecular evidence of honey used in religious offerings at a 6th century BCE Greek shrine in Paestum, southern Italy.

The underground shrine, located about 90 minutes from Pompeii, was discovered in 1954. Among its contents were several bronze vessels holding a sticky substance, long presumed to be honey based on ancient practices of offering honey to gods and the deceased. However, three separate investigations over 30 years failed to confirm this, instead suggesting the jars contained animal or vegetable fats mixed with pollen and insect fragments.

Using modern analytical techniques, Oxford researchers have now uncovered the true nature of the substance. Employing tools like protein mass spectrometry, small-molecule analysis, and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy, the team detected a complex mix of sugars, organic acids, and royal jelly proteins — all consistent with modern beeswax and honeycomb.

“This research highlights the untapped scientific value of museum collections,” said Dr. Luciana da Costa Carvalho, co-lead of the study. “With modern tools and interdisciplinary collaboration, we can extract new information from old finds.”

Copper corrosion products found in the residue also played a role. The team suggests that copper ions may have protected the honey’s sugar compounds from microbial degradation, aiding their preservation over two millennia.

The study was made possible through collaboration with the Ashmolean Museum and the Archaeological Park of Pompeii. The contents of a Greek bronze hydria — one of the key vessels — were loaned for scientific analysis during preparations for the Ashmolean’s 2019 exhibition *Last Supper in Pompeii*.

As part of the exhibit's conservation efforts, 37 objects underwent detailed analysis. Some revealed soot on their bases, indicating use over open flames, while others contained interior limescale, pointing to their use as water-heating vessels.

A breakthrough came with the identification of major royal jelly proteins unique to honeybees. “This confirms the power of combining proteomics with metabolomics in archaeological research,” said co-author Elisabete Pires.

Dr. Gabriel Zuchtriegel, co-author and Director of the Archaeological Park of Pompeii, emphasized the broader implications: “This kind of scientific work allows for a more nuanced understanding of ancient lives and rituals — often from artefacts already sitting in museum storage.”

The researchers hope their findings will encourage further re-analysis of legacy archaeological materials, especially where past tests yielded ambiguous results.

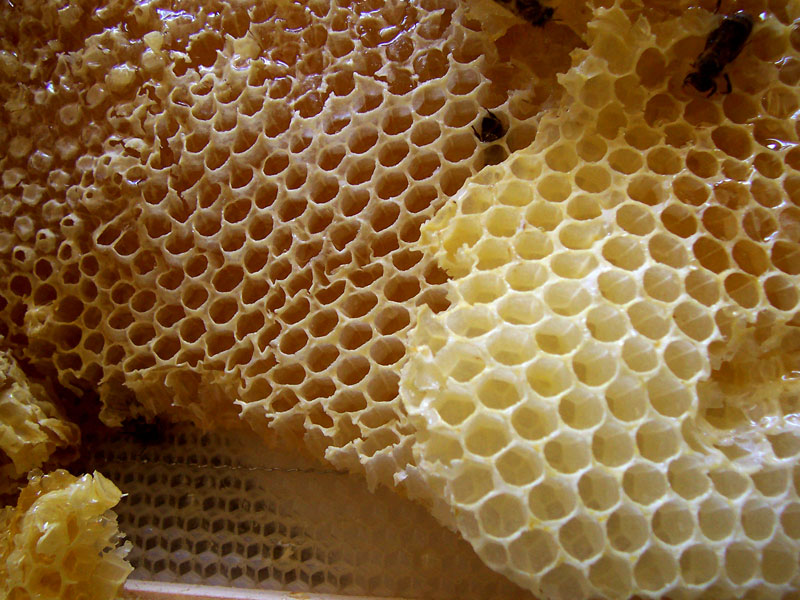

The full study, “A Symbol of Immortality: Evidence of Honey in Bronze Jars Found in a Paestum Shrine Dating to 530–510 BCE,” is available in the “Journal of the American Chemical Society”. Photo by Merdal z tureckiej Wikipedii, Wikimedia commons.