A team led by the British Museum has uncovered what is now the earliest known evidence of humans deliberately making fire—dating back around 400,000 years—at a site in Barnham,

Suffolk. The finding pushes back the timeline for fire-making by roughly 350,000 years, far earlier than the previously accepted benchmark of 50,000 years.

Published today in "Nature", the research marks a major shift in understanding a key evolutionary milestone. While early humans in Africa appear to have used naturally occurring fires more than a million years ago, this is the first clear proof of fire creation and control, a technological leap with profound implications for human development.

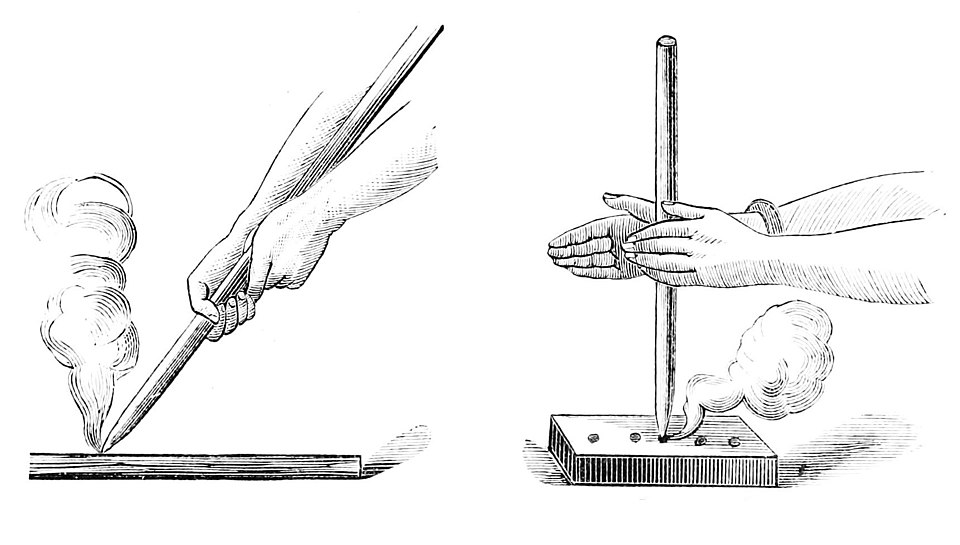

The evidence, likely left by some of the earliest Neanderthal groups, includes a patch of intensely heated clay, heat-shattered flint handaxes and two pieces of iron pyrite—an iron sulfide mineral used historically to generate sparks when struck against flint. Because pyrite is rare in the local landscape, researchers believe these early humans understood both its properties and where to source it.

It took four years for lead researchers Nick Ashton and Rob Davis to rule out naturally occurring wildfires. Geochemical analysis shows the burned sediments reached temperatures above 700°C, with repeated burning in the same spot—strongly indicating a controlled hearth used multiple times.

Mastering fire-making transformed early human life. It enabled survival in colder climates, expanded edible food sources through cooking, and reduced reliance on unpredictable natural fires. Cooked roots, tubers and meat improved nutrition and digestion, helping free energy to support growing brains. Fire also became a social anchor: a place for gathering after dark, sharing information, strengthening relationships and developing language and storytelling.

Because ash, charcoal and baked sediments often erode or scatter, direct evidence of ancient fire use is exceptionally rare. Yet discoveries across the UK, France and Portugal indicate fire became increasingly central to human behaviour between 500,000 and 400,000 years ago. The Barnham site now offers a crucial explanation for this shift—the emergence of intentional fire-making itself.

Professor Nick Ashton, Curator of Palaeolithic Collections at the British Museum, said: "This is the most remarkable discovery of my career, and I'm very proud of the teamwork that it has taken to reach this groundbreaking conclusion.

'It's incredible that some of the oldest groups of Neanderthals had the knowledge of the properties of flint, pyrite and tinder at such an early date".

Dr Rob Davis, Project Curator: Pathways to Ancient Britain at the British Museum, said: "The implications are enormous. The ability to create and control fire is one of the most important turning points in human history with practical and social benefits that changed human evolution.

'This extraordinary discovery pushes this turning point back by some 350,000 years."

Professor Chris Stringer, Natural History Museum, said: "The people who made fire at Barnham at 400,000 years ago were probably early Neanderthals, based on the morphology of fossils around the same age from Swanscombe, Kent, and Atapuerca in Spain, who even preserve early Neanderthal DNA."

The work involved colleagues from the Natural History Museum, London, Queen Mary University of London, University College London, the University of Liverpool and Leiden University. Photo by Wikimedia commons.