On a hot summer afternoon in Tehran, the Boof Cafe offers a cool respite with its distinctive iced Americanos—perhaps the most unique in the city. Nestled in a leafy corner of the old,

now-defunct US embassy compound, the cafe’s quiet charm contrasts starkly with its turbulent backdrop.

Outside, the embassy's towering concrete walls are still covered in anti-American murals—remnants of the broken diplomatic ties since the 1979 Iranian Revolution and the US embassy hostage crisis. Inside, barista Amir serves coffee beneath a sign that reads: "Keep calm and drink coffee."

"I hope relations between the US and Iran improve," Amir says, pouring another drink. "Sanctions hurt our businesses and limit our freedom to travel."

Only two tables are occupied: one by a woman in a traditional black chador, the other by a young couple—she in jeans with flowing hair, he with his arm around her. It’s a snapshot of the complex contradictions shaping Iran’s capital today.

Meanwhile, at the headquarters of Iran's state broadcaster IRIB, a somber scene unfolds. A taped speech by Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei plays on a small screen—the only piece of equipment still functioning in the bomb-ravaged complex.

"The Americans have always opposed the Islamic Republic," the 86-year-old leader declares. He is rumored to have taken shelter in a bunker following Israel’s wave of strikes targeting Iran’s nuclear and military infrastructure.

The devastation at the IRIB compound is severe. An Israeli missile struck on June 16, igniting a fire that gutted the studio meant to air the Supreme Leader’s speech. Now, only a skeleton of steel remains, littered with melted cameras, shattered glass, and scorched debris. Israel claimed it was targeting a propaganda hub embedded with military functions—claims Iranian journalists reject.

This damage has come to symbolize a dark chapter for Iran.

In Tehran’s hospitals, the human toll is just as visible. At Taleghani General Hospital, head nurse Ashraf Barghi is still treating victims of the conflict.

“I’m scared it’s not really over,” she says. “We don’t trust the ceasefire will hold.”

On June 23, when Israel struck near the notorious Evin prison—where many political prisoners are held—both civilians and soldiers flooded into Barghi’s emergency ward.

“These were the worst injuries I’ve seen in 32 years,” she recalls, visibly shaken.

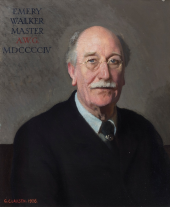

One of her patients, Morteza, was working in the prison’s transport unit when the missile hit. Lying in a hospital bed, he reveals injuries to his arms and lower body. “Israel claims they only hit military targets, but that’s a lie,” he insists. Photo by Sasan Geranmehr, Wikimedia commons.

Next door, wounded soldiers are recovering—though journalists are barred from entering.

Across the capital, the full impact is becoming clear. The Iranian health ministry reports 627 people killed and nearly 5,000 injured during the 12-day conflict.

Now, Tehran is cautiously returning to its routines. Traffic is picking up, shops in the city's iconic bazaars are reopening, and people are returning after fleeing the violence. But beneath the surface, the trauma lingers.

“They were terrible days,” says Mina, a young woman who breaks into tears as she tries to express her sorrow. “We worked so hard for a better life, but now we don’t see any future.”

We meet at the base of the Azadi Tower—an iconic monument where crowds gathered for an open-air concert by the Tehran Symphony Orchestra. The event was meant to offer solace, but the tension in the air remains.

Among the audience, both critics and supporters of Iran’s leadership stood together, united by uncertainty about what comes next.

“The government has to listen to the people,” says Ali Reza. “All we want is more freedom.”

Eighteen-year-old Hamed adds with quiet defiance, “Attacking our nuclear facilities just to prove a point isn’t diplomacy.”

Despite the tight constraints of daily life, Iranians continue to speak out. With eyes on their own leaders, and those in Washington, many wait anxiously—knowing that the next decision could again reshape everything.