The UK’s seas have just experienced their warmest January–July on record, with average surface temperatures more than 0.2°C higher than any year since 1980, according to provisional

Met Office data. Though the increase might sound small, decades of gradual warming—driven by fossil fuel emissions—are reshaping marine life.

Warmer waters are inviting unexpected guests like octopus, bluefin tuna, and mauve stinger jellyfish, while cold-water species such as cod and wolf-fish retreat north. Marine biologist Dr. Bryce Stewart likens the surge of heat-loving species to a “canary in the coal mine” for ecosystem change.

In Cornwall, snorkeler Heather Hamilton has swum through glowing chains of salps—transparent, jellyfish-like creatures—once rare in UK waters but now increasingly common. Off the southwest coast, bluefin tuna sightings have soared, thrilling anglers like 19-year-old Harry Polkinghorne, who describes their feeding frenzies as “like watching a washing machine in the water.”

However, the changes bring challenges. In Whitstable, fisherman Ben Cooper has seen his main catch—cold-water whelks—suffer mass die-offs during heatwaves. He remembers when cod was the staple catch, before warming seas drove them away.

Marine heatwaves, now more frequent and intense, have persisted around parts of the UK for much of 2025, following unusually hot seas in 2023 and 2024. Experts warn that hotter oceans not only threaten marine life but also absorb less carbon dioxide, potentially accelerating global warming.

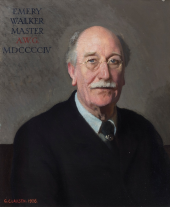

In the long run, both fishers and consumers may have to adapt to a new menu from UK seas. As Dr. Stewart puts it, “Ecosystems are in flux, and we’re watching the changes unfold in real time.” Photo by Mrs Blorenge, Wikimedia commons.