Media

-

Axel Springer backs Dovid Efune’s £500m Telegraph Bid, taking on Daily Mail owner DMGT

German media giant Axel Springer has thrown its weight behind a rival bid for Britain’s Telegraph Media Group, backing a £500 million offer led by U.S. publisher21 February 2026Read More...

Axel Springer backs Dovid Efune’s £500m Telegraph Bid, taking on Daily Mail owner DMGT

German media giant Axel Springer has thrown its weight behind a rival bid for Britain’s Telegraph Media Group, backing a £500 million offer led by U.S. publisher21 February 2026Read More... -

UK leads global fight against deepfakes with science-driven detection standards

Deepfakes—AI-generated videos, images and audio—are no longer a fringe curiosity. They are a fast-growing threat across the UK, exploited by criminals to scam victims out of money,19 February 2026Read More...

UK leads global fight against deepfakes with science-driven detection standards

Deepfakes—AI-generated videos, images and audio—are no longer a fringe curiosity. They are a fast-growing threat across the UK, exploited by criminals to scam victims out of money,19 February 2026Read More... -

Former Daily Mail editor Paul Dacre tells UK court he is “angry and upset” over Prince Harry privacy claims

Paul Dacre, the long-serving former editor of the Daily Mail and one of the most influential figures in British journalism, told the High Court in London that he felt11 February 2026Read More...

Former Daily Mail editor Paul Dacre tells UK court he is “angry and upset” over Prince Harry privacy claims

Paul Dacre, the long-serving former editor of the Daily Mail and one of the most influential figures in British journalism, told the High Court in London that he felt11 February 2026Read More... -

BBC TV licence fee to rise to £180 from April, sparking anger as costs overtake streaming rivals

The annual TV licence fee will rise by £5.50 to £180 from April 1, dealing another blow to household budgets already stretched by the cost-of-living crisis.06 February 2026Read More...

BBC TV licence fee to rise to £180 from April, sparking anger as costs overtake streaming rivals

The annual TV licence fee will rise by £5.50 to £180 from April 1, dealing another blow to household budgets already stretched by the cost-of-living crisis.06 February 2026Read More... -

Elton John’s husband David Furnish accuses Daily Mail of homophobia and privacy violations in High Court trial

David Furnish, the husband of British music icon Elton John, has accused the publisher of the Daily Mail of unlawfully obtaining private information about their06 February 2026Read More...

Elton John’s husband David Furnish accuses Daily Mail of homophobia and privacy violations in High Court trial

David Furnish, the husband of British music icon Elton John, has accused the publisher of the Daily Mail of unlawfully obtaining private information about their06 February 2026Read More...

Culture

-

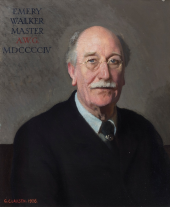

Emery Walker revealed: new exhibition explores the man behind the arts and crafts legend

A new exhibition opening this spring at Emery Walker’s House sets out to restore depth, warmth, and personality to one of Britain’s most influential yetRead More...

Emery Walker revealed: new exhibition explores the man behind the arts and crafts legend

A new exhibition opening this spring at Emery Walker’s House sets out to restore depth, warmth, and personality to one of Britain’s most influential yetRead More... -

London confirms St Patrick’s Day 2026 parade and Trafalgar Square festival

London will turn green once again next spring after the Mayor confirmed the capital’s St Patrick’s Day celebrations will take place on Sunday 15 March 2026, with aRead More...

London confirms St Patrick’s Day 2026 parade and Trafalgar Square festival

London will turn green once again next spring after the Mayor confirmed the capital’s St Patrick’s Day celebrations will take place on Sunday 15 March 2026, with aRead More... -

Masterpieces beyond the Museum: National Gallery brings life-size art to communities ccross the UK

World-famous paintings from the National Gallery are stepping out of Trafalgar Square and into everyday life, as part of a major touring project that will seeRead More...

Masterpieces beyond the Museum: National Gallery brings life-size art to communities ccross the UK

World-famous paintings from the National Gallery are stepping out of Trafalgar Square and into everyday life, as part of a major touring project that will seeRead More... -

Award-winning Polish writer Mariusz Szczygieł brings ‘Not There’ essay collection on UK tour

Polish writer Mariusz Szczygieł, one of Central Europe’s most acclaimed literary reporters, will tour the UK later this month with a series of public events marking the English-language release...Read More...

Award-winning Polish writer Mariusz Szczygieł brings ‘Not There’ essay collection on UK tour

Polish writer Mariusz Szczygieł, one of Central Europe’s most acclaimed literary reporters, will tour the UK later this month with a series of public events marking the English-language release...Read More... -

Professor Dame Carol Black GBE reappointed as Chair of the British Library for 2026–2027

The UK Secretary of State has confirmed the extension of Professor Dame Carol Black GBE as Chair of the British Library, continuing her leadership from 1 September 2026 to 31 August 2027.Read More...

Professor Dame Carol Black GBE reappointed as Chair of the British Library for 2026–2027

The UK Secretary of State has confirmed the extension of Professor Dame Carol Black GBE as Chair of the British Library, continuing her leadership from 1 September 2026 to 31 August 2027.Read More... -

Climate, community and care: Soma Surovi Jannat’s landmark exhibition at the Ashmolean Museum

From spring through autumn 2026, the Ashmolean Museum presents 'Soma Surovi Jannat: Climate Culture Care', a powerful new exhibition that places climateRead More...

Climate, community and care: Soma Surovi Jannat’s landmark exhibition at the Ashmolean Museum

From spring through autumn 2026, the Ashmolean Museum presents 'Soma Surovi Jannat: Climate Culture Care', a powerful new exhibition that places climateRead More... -

Londoners on trial: 700 years of crime revealed in a free City archives exhibition

From medieval pickpockets to notorious Victorian figures, seven centuries of crime, punishment and public fascination are laid bare in a new exhibition atRead More...

Londoners on trial: 700 years of crime revealed in a free City archives exhibition

From medieval pickpockets to notorious Victorian figures, seven centuries of crime, punishment and public fascination are laid bare in a new exhibition atRead More... -

Lost for centuries, Henry VIII’s golden love pendant finds a home at the British Museum

A golden heart pendant once symbolizing the doomed marriage of Henry VIII and Katherine of Aragon has finally been secured for permanent display at the BritishRead More...

Lost for centuries, Henry VIII’s golden love pendant finds a home at the British Museum

A golden heart pendant once symbolizing the doomed marriage of Henry VIII and Katherine of Aragon has finally been secured for permanent display at the BritishRead More... -

British High Commission hosts Caledonian Ball in Lahore to celebrate growing Scotland–Pakistan partnership

The British High Commission brought a touch of Scotland to Lahore this week as it hosted the Caledonian Ball at the historic Sir Ganga Ram Residence, celebratingRead More...

British High Commission hosts Caledonian Ball in Lahore to celebrate growing Scotland–Pakistan partnership

The British High Commission brought a touch of Scotland to Lahore this week as it hosted the Caledonian Ball at the historic Sir Ganga Ram Residence, celebratingRead More... -

300-year-old Rysbrack Marble putti blocked from export as UK scrambles to save national treasure

A three-century-old marble sculpture by renowned eighteenth-century sculptor Michael Rysbrack has been placed under a temporary UK export ban, giving BritishRead More...

300-year-old Rysbrack Marble putti blocked from export as UK scrambles to save national treasure

A three-century-old marble sculpture by renowned eighteenth-century sculptor Michael Rysbrack has been placed under a temporary UK export ban, giving BritishRead More... -

Inside ICG PR: how an international PR agency shapes reputation for luxury, fashion, and cultural brands

Interview: the co-founder of Iris Consulting Group Iryna Kotlyarevska on building global visibility with cultural intelligenceRead More...

Inside ICG PR: how an international PR agency shapes reputation for luxury, fashion, and cultural brands

Interview: the co-founder of Iris Consulting Group Iryna Kotlyarevska on building global visibility with cultural intelligenceRead More... -

London Zoo’s giraffes take centre stage in New London Underground poster celebrating 200 years of ZSL

London Zoo’s iconic giraffes have stepped into the spotlight with the launch of a striking new London Underground poster, marking the start of ZSL’s 200th anniversaryRead More...

London Zoo’s giraffes take centre stage in New London Underground poster celebrating 200 years of ZSL

London Zoo’s iconic giraffes have stepped into the spotlight with the launch of a striking new London Underground poster, marking the start of ZSL’s 200th anniversaryRead More...

British Queen celebrates

Most Read

- Teen held after US woman killed in London stabbings

- Heave-ho Harry! Prince prepares to join the walking wounded in ice trek to North Pole

- Football: Farhad Moshiri adamant Everton deal above board

- "Master of English Style". Interview with Designer Lydia Dart

- Letter to the Financial Times from Lord Mayor Alderman Michael Bear

Education

Around 12,000 young people in some of the most disadvantaged areas of the country will benefit from a wave of new free schools, another major step in this government’s work to raise school

Amutri, a specialized startup from Falmouth University, has secured a substantial grant of £492,000 from Innovate UK.

Amidst a return to pre-pandemic marking standards, Jewish schools are emerging as beacons of success, bucking the trend of A-level grade deflation across the nation. These schools are

UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak participated in the recitation of the Indian epic 'Ramayan,' led by spiritual leader Morari Bapu at an event held at Cambridge University on

The UK High Commission in Ottawa and Canada-based British entrepreneur and philanthropist David Briggs have announced that they have joined forces to create the

Young people across England are celebrating exam results this morning – with thousands of them moving on to university, apprenticeships and the world of work.

Non-teaching personnel, including learning support and janitorial staff, are set to go on strike in the coming month. Non-teaching staff members across 10 council areas in Scotland are gearing

In the landscape of global communication, English holds a commanding position, especially within the scientific arena. However, this linguistic advantage creates obstacles for researchers

University staff strikes are set to persist into September following the breakdown of negotiations with employers, as announced by the University and College Union (UCU).

Jude Lowson has been chosen to lead The King's School, Canterbury, marking a significant milestone as the institution's first female headteacher after an astonishing 1,425 years dominated by