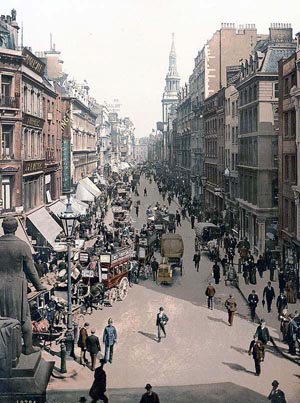

The streets of London were thick with beggars and confidence tricksters in Victorian times. In the 1880s 300,000 Londoners were classified as poor. Many beggars made desperate efforts to lift themselves and their families out of their unrelenting poverty by taking on a trade, however small and insignificant. They were reluctant to apply for Outdoor Relief under the Poor Law. The match sellers, shoe blacks and flower girls, very often displaced from the countryside where life was yet more unendurable, were given short shrift by many of the great and wealthy. An 1888 tourist guidebook suggested the following evasive action be taken by travellers: 'To get rid of your beggar, when wearisome, take no notice of him at all. He will only follow you till you meet a more likely person, but no farther'.

Street traders faced suspicion from the public and persecution by the police on a daily basis. Their lives were a constant struggle to win food and shelter; many lived in cheap, crowded lodging houses in poor areas of the West End and the City, where they were preyed upon mercilessly by voracious landlords. There was, of course, no social relief, and families had to rely on their wits to keep body and soul together.

The Victorian social critic Henry Mayhew reported that the chimney sweeps were a tight-knit community, and that master sweepers often let rooms to families in the same trade. The climbing boys, often from the workhouse, earned 2d or 3d a day, but were sometimes given an extra 6d by grateful householders. They climbed easily up through wide flues using their elbows, but often found themselves stuck and near-suffocated in narrow nine-inch chimneys. For young children it must have been the most terrifying experience. George Smart's invention of the familiar set of hollow rods topped with a broad bristle brush encouraged an end to the cruelty, and an Act of Parliament finally made child sweeps illegal in 1875.

There were once 2,500 cabinet-making shops in London, many employing children. When powered sawmills and mechanical production methods brought ready-made furniture onto the market, many thousands of craftsmen lost their jobs, and had to scratch a living by going door to door mending furniture or re-caning chairs.

The gingerbread man with his laden tray was a welcome sight to children. His dark-coloured cake of flour, treacle and ground ginger was a favourite snack with Victorians at fairs and street events. The roughly-shaped pieces were measured into paper cones and topped with a blanched almond. The gingerbread was probably made by his wife or daughters.

Sporting their red uniforms, the bootblack boys were a familiar sight on the streets of London. The bootblack business grew into a highly organised philanthropic affair: the Ragged Schools, Saffron Hill, set up the first society, and nine others followed. Their aim was to educate orphan boys and to give them a good start in the world; by the 1880s the shoeblack societies had 400 boys on their books. Members of the Shoeblack Brigade were licensed to trade by the Metropolitan Police and carried on their business unhindered.

Small children loved to cluster round the hokey-pokey stall licking at the cheap ice cream. The hokey-pokey men were usually Italian immigrants (during the winter they often worked as hurdy-gurdy men). Every morning in summer they froze the ice cream they had mixed the night before, and went their rounds crying: 'Gelati, ecco un poco!' ('Ice cream, here's a little!') - hence the slang words for ice cream. The hokey-pokey man sold his ice cream in small glasses, 'licks', which he wiped clean when his customers had finished with them. Edible ice cream cones began to be used in the 1890s. A popular nonsense rhyme in Victorian times ran:

'Hokey-pokey, pokey hump!

Hokey-pokey, a penny a lump.

Hokey-pokey, find a cake;

Hokey-pokey, boil and bake.

Here's the stuff to make your jump;

Hokey-pokey, penny a lump.

Hokey-pokey, sweet and cold,

For a penny, new or old.'

In almost every Victorian city street you could find a child selling matches. Bryant & May's matches, such as their fusee 'Alpine Vesuvian' matches, popularly known as Brimstones, were popular products. This was hardly a desirable job, but a match seller was considerably better off than those poor Londoners who were involved in the manufacturing of matches: the yellow phosphorus used in the process caused a debilitating disease of the mouth known as 'phossy jaw'. Bryant & May employed 700 girls in their match factories. In 1888 these girls went on strike for better pay and conditions, but such a protest and threat to public order was rare amongst workers in Victorian Britain.